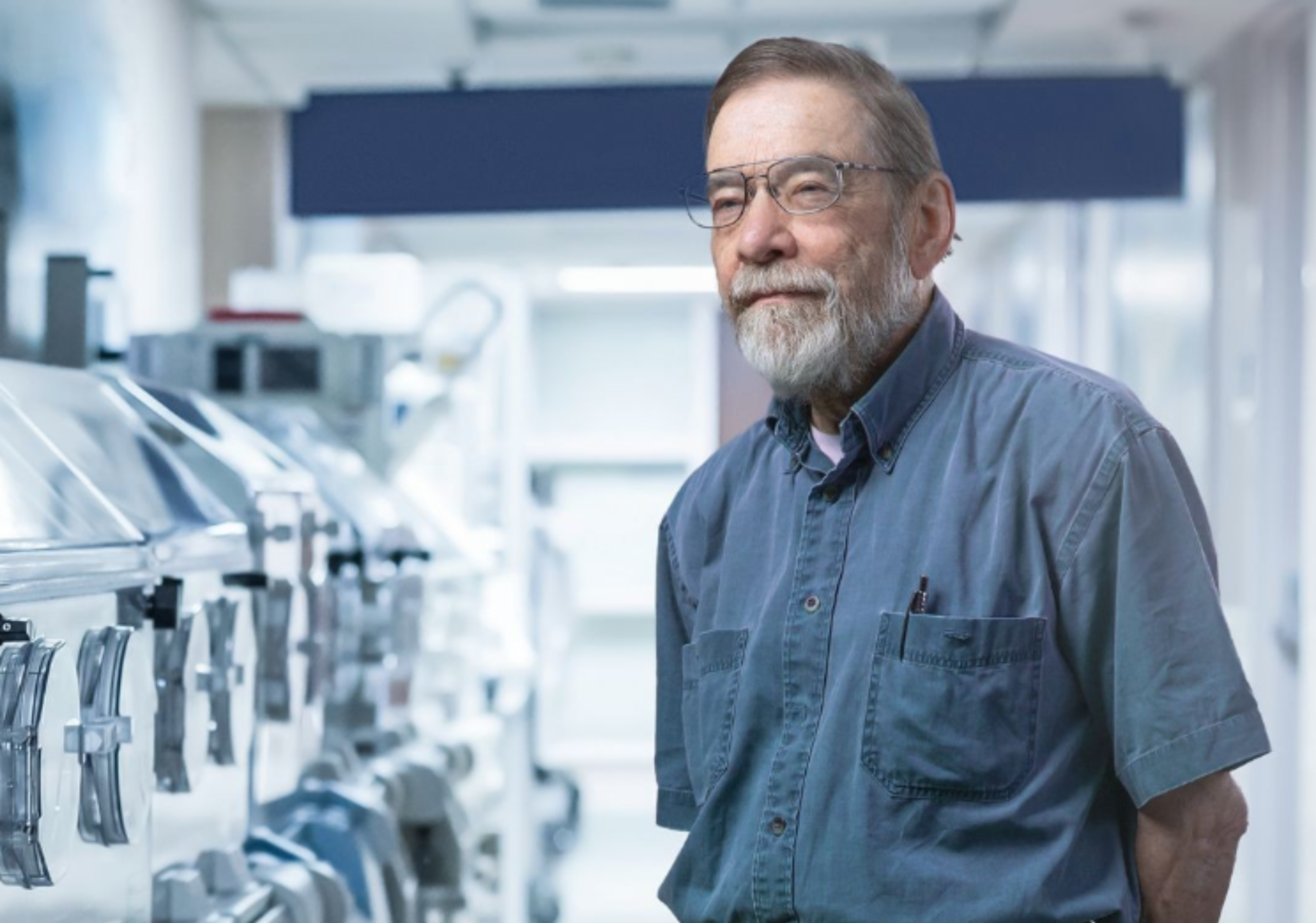

You may not know Dr. Fred Possmayer, but you may know someone because of Dr. Fred Possmayer.

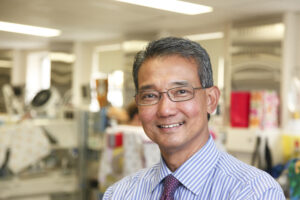

Picture this: It was a busy early morning in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) in London in 1982, 2 a.m. to be precise – Dr. Victor Han remembers it vividly.

He is now the Director of Children’s Health Research Institute (CHRI), but in 1982, Dr. Han was still a young paediatrician training to specialize in Neonatal Care. On that early morning over 40 years ago, he was the doctor on-call when a preterm baby on a ventilator went into respiratory failure — and Dr. Possmayer and he made medical history that changed the world’s standard of care for premature babies with respiratory distress.

Leading up to that early morning, Dr. Possmayer, a Professor in Biochemistry and Obstetrics & Gynaecology and his research team, including Dr. Han, Dr. Graham Chance and Dr. Paul Harding, had been working on a ground-breaking study treating premature infants with breathing difficulty called Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS) by administering a surfactant preparation into infants’ lungs.

What Makes Dr. Possmayer’s Surfactant Discovery So Important?

We all have surfactant in our lungs. It makes them elastic and keeps the air sacs, called alveoli, from collapsing. Without surfactant, lungs are stiff, making breathing very difficult. Surfactant is essential for effective respiration, but in premature infants, many have yet to develop cells in the lungs to make their own surfactant naturally. That’s why Dr. Possmayer was looking into using surfactant extracted from cows’ lungs as a temporary supplement until the babies develop their own.

Back in 1982, research into lung surfactant had progressed to the point of pre-clinical studies on rabbit pups which demonstrated prematurely delivered pups would survive when given surfactant, but it had not yet been tried on humans. There were still many questions to answer, like whether a surfactant preparation from cows’ lung washings would prove effective on a premature infant, or whether it might cause harmful side effects in humans.

The governing bodies of universities on Ethical Research Studies in Humans had approved its use as an experimental medication — but only in very sick or dying premature newborns as a “rescue therapy.”

On that fateful early morning in 1982, Dr. Han became the first physician to administer Dr. Possmayer’s surfactant preparation. As a baby in the NICU deteriorated further from respiratory distress, even with maximum settings on a ventilator, they approached the parents for their consent to try the experimental treatment. Understanding that this was their best hope, the parents gave the team permission to try.

After Dr. Han administered the preparation, he and the team watched the baby expectantly. To their consternation, the baby got worse instead of getting better.

“What have we done? Have we drowned the baby with the preparation we gave?” Dr. Han recalls thinking in those first several minutes after the experimental preparation was given in any baby.

Then, the baby got better slowly. The team watched as the baby’s blood oxygen levels and vitals slowly improved, even beyond the levels before receiving the surfactant. For a while, the surfactant worked, and the team learned that cow surfactant could indeed help human babies without causing negative reactions.

Sadly, the baby only survived for a few more hours. For preterm babies with RDS, breathing can be particularly challenging. Lungs are among the last organs to mature, and so many preterm babies need ventilators to help with breathing. Ventilators use positive pressure to inflate the lungs, and especially those back in the 1980s, damage the lungs even as they help the babies breathe. That, unfortunately, was the case for the first recipient of Dr. Possmayer’s surfactant preparation — the damage was already done. However, the team also learned that, perhaps, providing the surfactant earlier soon after a premature baby is born before ventilators have a chance to damage the fragile lungs would improve the effectiveness of the surfactant replacement therapy. The early use of surfactant was highly successful in clinical trials and has since remained the standard of care.

More Discoveries Were Still To Be Made

Seven years later, Dr. Han, now a neonatologist in the London NICU at St. Joseph’s Health Care, made another discovery with Dr. Possmayer’s surfactant preparation, now called bovine lipid extract surfactant (BLES). In 1989, a very premature baby named Tyler, whose parents were from Windsor, was born in London and Dr. Han and his team provided BLES early in Tyler’s life, which improved his breathing initially. However, a day later, he developed severe breathing problems, this time because of bleeding into the lungs called acute pulmonary hemorrhage. Tyler was in grave danger.

Dr. Han approached Tyler’s parents about trying a second dose of surfactant, which at that time had not been tried for pulmonary hemorrhage. It was based on Dr. Possmayer’s research, which demonstrated in a laboratory setting that proteins in the lung’s alveoli like blood, meconium or infection can rapidly inactivate surfactant, and these babies would go back into respiratory distress and possibly die. Dr. Han assessed that bleeding into the lungs was the possible reason for Tyler’s deterioration. Tyler’s parents gave their consent for this yet-to-be-approved indication. Soon after the second dose of surfactant, Tyler’s respiration gradually improved. Within three weeks, he was well enough to be removed from the ventilator.

Today, Tyler is a grown man, healthy, married, and holding a degree from Wayne State University. His mother, Ann, still sends Dr. Han annual updates on Tyler at Christmas time.

“Ann attributes her son’s life to me, but I always tell her that it was Dr. Possmayer’s surfactant that saved her son’s life,” Dr. Han says.

A subsequent dose of surfactant for babies who are in respiratory failure due to pulmonary hemorrhage, meconium aspiration or pneumonia is now an acceptable indication for a further dose of surfactant by many governing bodies like Canadian and American Pediatric Societies.

A Life-Saving Legacy Like Few Others

Dr. Possmayer’s BLES has become the standard of care for preterm babies in Ontario, Canada, and around the world. NICUs across the nation keep it on hand, as do emergency transport teams in Ontario and Canada, who use it to stabilize premature infants in respiratory distress born remotely before they make it to a higher level NICU.

As medical discoveries go, few have been as impactful as Dr. Possmayer’s work on BLES. In 2009, the Canadian Medical Association Journal and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research named it one of the top eight achievements in Canadian health research. In 2015, a province-wide poll by the Council of Ontario Universities saw Dr. Possmayer’s work recognized as a top-five game-changing research breakthrough. It’s often referred to in the same breath as the discovery of insulin.

As with insulin, Dr. Possmayer’s surfactant preparation has saved thousands of lives around the world. NICU respiratory therapists and nurses often refer to it as “BLESS” because of its almost miraculous effect, reducing preterm infant mortality by two-thirds. For a time, Dr. Possmayer worked on the production BLES through a company he started here in London, called BLES Biochemicals. When he needed to move back to basic laboratory-based research, he sold his patent on the method of extracting surfactant from cows’ lung washings to his long-time research associates for $1 each, with the understanding that they would charge the lowest price possible to NICUs for the product.

As Dr. Han says, that’s the kind of man Dr. Possmayer is. “The nicest person you will meet. He is the most unassuming, the most humble, and would never take full credit for all of his achievements. He would always share credit with his colleagues and collaborators.”

Over 40 years after Dr. Han first administered it, BLES Biochemicals — under the leadership of Dr. Possmayer’s colleagues — continues to produce the preparation in London, ON, using Dr. Possmayer’s original preparation method, distributing it to NICUs around the world, including many developing nations, at affordable prices.

“It’s an honour and a privilege for me to be involved in surfactant research in the beginnings when there were still lots of unknowns and questions, before it became the standard of care for premature babies around the world. I was lucky to be the right person at the right place at the right time,” Dr. Han says.

Dr. Possmayer continues to advance research both as a mentor and in his own work. As a Professor Emeritus of Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University and a researcher at Children’s Health Research Institute at Lawson, Dr. Possmayer remains an active force, as well as an inspiration to many researchers at CHRI and Western.

In 2024, Dr. Possmayer received an appointment to the Order of Ontario, which is the province’s highest civilian honour, in recognition of his discovery of the method of and preparing large quantities of surfactant and its legacy. In its announcement, the Lieutenant Governor’s Office wrote that “Dr. Possmayer’s gift of life to children around the world is incalculable.”

Dr. Possmayer’s work also serves as a reminder of the importance of supporting research as an investment in the future of care. Solutions like BLES that have saved countless infants’ lives and reduced suffering around the world are being researched at CHRI. Many other discoveries are on the pipeline to be translated to the bedside, and many are just around the corner.

Featured photo credit: Schulich Medicine and Dentistry Communications